By Claire Cloutier, Team FSO contributing writer

Photos by Robin Ritoss, Jordan Cowan (On Ice Perspectives) and Deanna Stellato-Dudek

In 2016, Deanna Stellato-Dudek came back to competitive figure skating because she had unfinished business with the sport. Her singles career ended prematurely in 2001, due to injury. But Stellato-Dudek realized she still wanted to skate and accomplish more, so she started pairs skating with Nate Bartholomay. She had big ambitions.

In 2016, Deanna Stellato-Dudek came back to competitive figure skating because she had unfinished business with the sport. Her singles career ended prematurely in 2001, due to injury. But Stellato-Dudek realized she still wanted to skate and accomplish more, so she started pairs skating with Nate Bartholomay. She had big ambitions.

“I want to win. I want to come home with hardware around my neck,” Stellato-Dudek said back in 2018. She and Bartholomay won several Challenger Series medals and were two-time U.S. bronze medalists, but ended their partnership in 2019.

Now, three and a half years later, Stellato-Dudek has another partner–Maxime Deschamps–and represents Canada. At 39, she’s still as dedicated to the sport as ever.

“There’s no age limit on passion. I love to go into the rink every day,” Stellato-Dudek said. “I love the daily grind, I love training, I love the challenge of competition.”

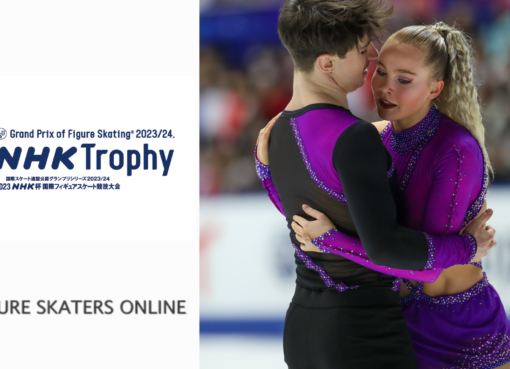

Stellato-Dudek and Deschamps initially teamed up in mid-2019. This season, they’re achieving the results that Stellato-Dudek hoped for when she started pairs. The duo won their first international title at Nebelhorn Trophy in September and their first Grand Prix medal (silver) at Skate America in October. This weekend, they’re favored to win another medal at the Grand Prix de France.

Although their results are satisfying, Stellato-Dudek and Deschamps also have an appreciation for the journey of skating and for other achievements in the sport. When Figure Skaters Online (FSO) spoke with them at Skate America, they said their ultimate goal this season is to simply be their best selves on the ice and keep improving. They talked about how their partnership started, what their day-to-day training is like, and how they developed their own signature element in pairs skating, the double forward death spiral.

The beginning

FSO: Deanna, you competed internationally in singles at the junior and senior levels from the late 1990s to 2000. Maxime, did you ever see Deanna compete back then?

FSO: Deanna, you competed internationally in singles at the junior and senior levels from the late 1990s to 2000. Maxime, did you ever see Deanna compete back then?

Deschamps: I started watching skating around the 2002 Olympics. Before that, I was just skating for fun. I started skating around four or five years old, and started private lessons [at] eight years old.

Stellato-Dudek: He never saw me. Because I was gone by 2002. He missed the first iteration. [Laughs] He got all his jumps later. Or what we would consider later, in the [United] States.

FSO: How did you meet up, and how did your partnership start?

Stellato-Dudek: After Nate and I decided we were going to part ways, I started looking around for other partners. I was contacting all the coaches I knew. You never know where the next person is. There’s so much mix-and-matching, in terms of countries and people coming together in pairs and ice dance, because it’s such a small subset of people who are at a certain level. So I contacted everyone. And Bruno Marcotte and Meagan Duhamel were like, ‘Oh, we have the perfect person for you, but he’s skating with somebody else.’ So I kept on looking. Maybe four months later, that partnership had dissolved. Bruno, who was Max’s coach at the time, asked, ‘Are you still looking for a partner? Do you want to come and have a chat with Max? He was the person I was telling you about, and he’s available.’ I was like, ‘Yes, absolutely.’

I was supposed to have a couple tryouts in Canada. Max was my first one. When we got together, we did a death spiral and a pairs spin, and he pulled me off my feet in both. I was so surprised. It’s one thing to be strong, but it’s a different thing to have power–that explosiveness. Those are two separate things.

We had a great tryout over the next couple of days. I was supposed to go have other tryouts, and we decided against it. We said: ‘No, this is it, we’re going to go forward.’ We both have long torsos, short legs. We’re both very strong, very powerful, and we both have the same goal–the Olympics–which is very important. It was a match right away. So I canceled all the other tryouts and stayed in Quebec. [Deschamps’s training base was in Montreal.] Those other places, I could have spoken English. Montreal, it’s French-only.

FSO: Bruno Marcotte was Max’s coach at the time. Did you consider moving to Oakville, Ontario, with him and Meagan?

Stellato-Dudek: We did think about that. But Max has a skating school in Montreal. At one point, he had 42 kids that he taught. So he’s a full-time coach. He needed that income, especially because we wouldn’t get any funding, since I wasn’t going to be released [from the U.S.] for a couple years. It wasn’t a financial option to leave. It just wasn’t monetarily possible. But we’re always happy to see Bruno at events, and he’s always super-positive and very encouraging to us.

FSO: What about citizenship issues? How did that play into the decision to become partners?

Stellato-Dudek: I called my contacts [in the U.S.] and asked how long it would take for a Canadian citizen to get American citizenship. They said, impossible by 2022, and highly unlikely by 2026. Max has some contacts in Canada, and he did the same. They said, highly unlikely by 2022, but likely by 2026. That’s what made our decision of what country we were going to. The Olympics was the big goal. We both want to go to the Olympics. So that was the deciding factor; what country we could possibly get citizenship from in time.

FSO: You mentioned your release from the U.S. How did that work?

Stellato-Dudek: The rules are pretty standard. They’re set in stone, for the most part. How long your wait time is depends on where you placed [at events], or if you’ve been to a Worlds, or a Four Continents. The rules are pretty similar in Canada also. It was going to be two years before they would release me. My last [international] competition with Nate was technically in 2018, but that didn’t matter. It had to be until the season [2018-19] was concluded. It’s not like two years to the date [of your last competition]. It’s two full seasons, which were 2019-20 and 2020-21, until I could compete [for Canada].

The pandemic

FSO: So from the start, you were looking at this as a long-term endeavor.

FSO: So from the start, you were looking at this as a long-term endeavor.

Stellato-Dudek: Yes. COVID-19 ate into so much of that waiting time, anyway. When it began in March 2020, there were shutdowns. We were off the ice for a full four months before we got back on. Every province sets their own rules, just like states [in the U.S.]. In January 2021, the COVID numbers got bad again, so Quebec shut everything down. Only [skaters] that they considered to be ‘excellent’ skaters were allowed to continue. Those were skaters on the national team, who competed internationally. And I wasn’t released, so I wasn’t one of those skaters. We were off again in January, February, and March 2021. It was really brutal.

FSO: How did the pandemic affect you, in terms of being able to visit family and friends in the U.S.?

Stellato-Dudek: The border was closed, and I couldn’t have any friends or family visit. And I couldn’t leave, because I didn’t have my [Canadian] citizenship to get back. I felt like I was in a cage. I wasn’t allowed to leave; I couldn’t see any of my loved ones. I couldn’t skate, which is what I went there for. For me, personally, it was a very hard time. Talk about questioning your decisions; I was really questioning my decisions. Waiting for this to pass and be over and have some semblance of normalcy again. Just being able to skate every day. Then we got back on the ice, and we had to wear masks. I said, Whatever, fine, I’ll take it. It was tough, for sure. Some people had it worse than me. But it was definitely unusual circumstances. Max’s family was there. [Deschamps’s family lives in Montreal.] Any time that he would see them, they would invite me. They tried to include me in everything. His mom didn’t really speak any English when I met her, but she’s been practicing. With my broken French and her broken English, we can make a conversation.

FSO: And you’ve learned a little French, too?

Stellato-Dudek: Yes, a little. French is very difficult, but I know many words. I can speak it easier than I can understand it. I have a hard time with listening and being able to compute that speech in my brain. I’m comfortable around Max, because he understands my French. But in an interview, or something like that, I’d be petrified to speak French.

Deschamps: Deanna is way better than she thinks. She always sees herself as less good [perfectionist]. In everything. [Smiles at Stellato-Dudek]

FSO: How do you like coaching, Maxime?

Deschamps: I love it. I coach every level. I coach adults, kids who just started to learn skating, special Olympics [special needs], even people I compete with.

Stellato-Dudek: He’s very good at it. He went to college for biomechanics and kinesiology. He’s the one who taught me the forward outside death spiral. He really has a knack for coaching. I think when we’re finished with our careers, you’ll see him a lot at the boards.

FSO: Deanna, do you also coach?

Stellato-Dudek: I can’t work, legally, because I don’t have my equivalent of a green card in Canada. So I volunteer sometimes, helping him coach. I also volunteer at our rink, helping some of our other pairs teams. Otherwise, I seem to always be busy, managing things or helping my family out from home. I’m never at a loss for having stuff to do. I need to [save] energy for when we train. Because we give our all to it, and it’s really draining.

The double forward death spiral

FSO: You mentioned the forward outside death spiral, which is a really cool-looking element for you. Tell me how you developed this element.

FSO: You mentioned the forward outside death spiral, which is a really cool-looking element for you. Tell me how you developed this element.

Stellato-Dudek: When Max and I were off the ice for the second COVID shutdown [early 2021], we thought, What can we do, on these small frozen ponds in Quebec, that can up our points? And it was the forward outside death spiral. That’s how that was born–out of what could we do, with what we were being given–which was not a lot. When I first learned, it took a while. The first day I did one and didn’t fall, I threw my arms up like I landed a jump or something. I was so excited.

Last season, we did the forward outside death spiral with a normal backward outside pivot.

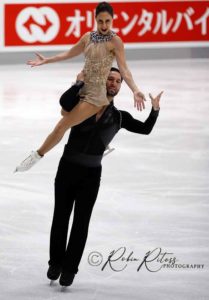

There were only a few teams that did it-–Pavliuchenko/Khodykin, Sui/Han, Peng/Jin, and Max and I. I did the same position as Sui/Han and Peng/Jin, and it wasn’t well-received. People just don’t like that bent-leg position. So we were like: How can we take it up a notch? I’m letting my leg be extended. And Max had the idea of a forward pivot.

That was another huge learning curve. The center of gravity is different when you’re doing a forward pivot. He has to move his body almost in a circular motion to create the tension, to keep it turning. We didn’t even know if this was possible, because no one had done it before. But we thought, Let’s try it. Let’s try to do something where, maybe in 10 years, someone will be watching us and trying to do what we did. It’s the first time in skating history.

We talked with some ISU technical [representatives], to discuss this pivot being allowed [and to get approval]. I said: ‘You know, everyone wants to win the Olympic gold medal, to win a World championship, to have a medal at a major event. But it only happens to three teams [per event]. That’s it. There are other ways to leave your mark on a sport.’

Doing something where we’re being innovative and original and the first ones to do a double forward death spiral–forward outside and forward pivot–is special in its own right. It’s something [through which] we can put our stamp on pairs skating. Back in the 1990s, they had all those pro-am competitions, and I remember some of those pairs teams, and they did really cool things–very innovative lifts and in-between steps. They never won a World championship, but I remember them and their programs. There’s other ways to make your mark on the sport. So that’s what we’re trying to do.

Their training days

FSO: Deanna, in the press conference at Skate America, you mentioned that an average day for you includes five hours of exercise and three hours of cool-down routine. Did I hear that right?

FSO: Deanna, in the press conference at Skate America, you mentioned that an average day for you includes five hours of exercise and three hours of cool-down routine. Did I hear that right?

Stellato-Dudek: That’s 100 percent correct. We have off-ice in the morning, then we have three hours of on-ice every day, sometimes more. And we have an hour and a half of gym. Then I’ll go home and eat something, and I’ll start my official cool-down process. I do some yoga. I have suction cups that I move across my legs to do fascia [connective tissue] release, which helps your muscles not tense up the next day. I have Hyperlce Normatec [massage] pants, and I use a massage gun. I have a full three-hour routine that I do every night. I really am convinced that not only does it keep me fresh, as the week goes on, but it’s also kept me healthy.

I’ve been very lucky. Knock on wood. Our coach, Josee [Picard], jokes that I’m the least injured person in the rink, and I’m the oldest by far. Every time I feel a little something, I nip it in the bud. I go home, I treat it, and within 24 to 48 hours, it’s gone. If it’s not, I’m going to the physical therapist right away. It’s like immediate damage control. Because I know that if I had an ache or a pain that I let go, and then it got worse, it’s going to take me longer for it to heal and get better. Just because of physics, because I’m 39. And we just don’t have that kind of time, so I have to stay on top of it. And I knew when I came back that this was not going to be an option for me [to skip cool-down]. When I was a kid, sometimes I didn’t stretch when I was done, and it didn’t affect me the next day. Now it does.

Deschamps: She almost has more stuff than a physical therapist.

Stellato-Dudek: Yes, I almost have like a full physical therapy office in my apartment. [Laughs] To me, it’s necessary. It’s a big commitment, just to maintain my body. People like Tom Brady and even Floyd Mayweather, Jr., who’s done boxing into his 40s, they talk about this too. They have a lot more money than me, so they go to see professionals. Tom Brady has an acupuncturist on his staff. I have to kind of make my way, do it myself. But I have to do the same thing. If they’re doing it, at that level, and I’m close to their age, I have to do the same thing.

FSO: You are now coached by Josee Picard?

FSO: You are now coached by Josee Picard?

Stellato-Dudek: Yes, Josee Picard is our head coach. And we still work with Ian Connelly; he’s at our rink. Julie Marcotte is our choreographer. We work with Igor Tchiniaev for stroking and projecting, and things like that. He was an ice dancer in Russia, and he’s super-helpful. We have a jump coach, a coach for spins, and an off-ice ballroom coach whom we work with once a week. They say it takes a village, and it really does. I love the specificity of it–when you’re working on just a spin for half an hour, and that’s all you’re focused on. And you’re not having to worry about the jump, or the throw. When I went to Canada, I said I was going to throw myself into this process. Because they’ve had such a long pedigree of top pairs teams.

Their plans

FSO: What are your goals for this season, and afterward?

Deschamps: For this season, our main goal is just to increase our score. To just be our own selves. That’s how we’re going to build to a higher ranking internationally. The main goal is to just be our own selves every time we go out there.

Stellato-Dudek: We are just trying to increase our scores, increase levels. We want to just inch up our score at every event. And we did that here [at Skate America]. We got a higher score than at Oberstdorf [Nebelhorn]. So hopefully in France, we can get a little higher. Just every time, crawl up a little bit.

That’s what our goal is. We’re trying not to get too caught up in anything else. All you can do is go out there and do your best. Goodness knows, none of us go out there and try to do badly. No skater goes out there trying to fail. We’re just trying to find the positives in every performance, and get our levels and our scores where we want them.