By Scott Mammoser, Team FSO contributing writer

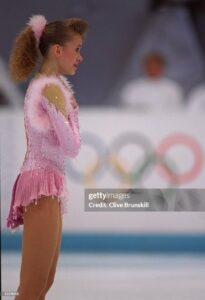

Photos courtesy Oksana Baiul-Farina and Getty Images by Clive Brunskill, David Madison and Pascal Rondeau/ALLSPORT

There are two distinct moments set under bright lights that Oksana Baiul-Farina remembers with great emotion. The first was when she took the ice before winning the gold medal at the 1994 Lillehammer Olympics. The second was when she gave birth to her daughter Sophia.

There are two distinct moments set under bright lights that Oksana Baiul-Farina remembers with great emotion. The first was when she took the ice before winning the gold medal at the 1994 Lillehammer Olympics. The second was when she gave birth to her daughter Sophia.

Thirty years have passed since the 16-year-old from Dnipro, Ukraine, stole the hearts of the world. Her Swan Lake short program complemented with her free skate to the sounds of Broadway are two of the most iconic in figure skating history. Today, the 46-year-old resides in Shreveport, La., with her husband and daughter – who will turn nine later this year.

“She likes artistic experiences – that’s what makes her happy,” Baiul-Farina said about her daughter in a phone interview. “And skating is one of them.”

A video surfaced of the family flooding their driveway this winter, giving Sophia a chance to emulate her mother.

“It never snows in Louisiana, but it did,” Baiul-Farina added. “So she enjoyed putting her skates on and skated for a few days.”

Baiul-Farina noted that Sophia watched her mother’s Olympic programs just before Christmas this year. If you watched the performances originally on CBS in 1994, you weren’t alone. Nearly 80 million Americans tuned in, as Baiul-Farina accomplished what foreign Olympic athletes rarely do. She broke the divide into mainstream U.S. celebrity culture.

“It’s been quite a ride,” she continued. “It was the most rewarding experience. Young skaters spend so much time at the ice rink, and that is what I did. I enjoyed what I was doing so much. I just felt like I am doing something that I really love. I know the younger generation, when they skate, it’s a lot of time, a lot of hours, a lot of dedication to get to a national level, let alone the Olympic level.”

A new era in Lillehammer

While former Soviet nations competed under the Unified Team banner at Albertville in 1992, the Lillehammer Games marked the first time athletes represented independent states, such as Ukraine and Belarus. Pairs and ice dance teams from the USSR dominated throughout its history, but a gold in singles skating was elusive until Ukraine’s Viktor Petrenko’s in 1992. Petrenko introduced Baiul-Farina to coach Galina Zmievskaya, and they trained together in Odesa, Ukraine. Soon after, 15-year-old Baiul-Farina won the 1993 world title in Prague – just two months after the newly-formed Czech Republic’s independence.

While former Soviet nations competed under the Unified Team banner at Albertville in 1992, the Lillehammer Games marked the first time athletes represented independent states, such as Ukraine and Belarus. Pairs and ice dance teams from the USSR dominated throughout its history, but a gold in singles skating was elusive until Ukraine’s Viktor Petrenko’s in 1992. Petrenko introduced Baiul-Farina to coach Galina Zmievskaya, and they trained together in Odesa, Ukraine. Soon after, 15-year-old Baiul-Farina won the 1993 world title in Prague – just two months after the newly-formed Czech Republic’s independence.

However, even with the reigning world title to her credits, drama between the U.S.’s Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding would overshadow Baiul-Farina heading into Lillehammer.

“At the Olympics,” Baiul-Farina remembered, “the scandal was between Tonya and Nancy, and no one really paid attention to me. Let alone I was already a world champion. I didn’t feel like I would be competing for an Olympic medal. I was just sharing my talent with people. When I was injured the day before, I had no clue if I could pull it off or not. I said I will, but talk is cheap. You never know until you actually do it. If you watch the footage, right after my combination jump in the end, I just put my hands up and said ‘Thank You God,’ and that is when I started crying. My mother died when I was 13 years old, and I honestly believed she was helping me from up above. I also believe a lot of lessons we learn in life, they come from good experiences and bad experiences.”

Seeing the light

The Olympic Amphitheatre in Hamar, Norway, pales in size to some of the arenas that host modern elite events. Now called CC Amfi, the venue permits only 6,000 seats. But when you approach the rink, the history is in the air.

“I remember when I walked into that building, there was so much chaos,” Baiul-Farina reminisced. “Tonya was running off the ice to her dressing room, and the camera was running behind her. She was in the dressing room, and I chose to go into the male dressing room. I chose to have my privacy away from the chaos. After the warm up, I was skating third- after Nancy.

“I remember the lights in that building. It’s not a big building, it’s fairly small in comparison to when I skate in America – they are 22,000 seat arenas. The lights are much lower to the ice, so it was bright as hell. The second time around, I saw those bright lights when I was giving birth to my baby. These are my two loves: the lights of that building and the birth of my daughter are two bright lights. The first time in my life when I saw that light, I knew my life would change forever, but you can’t pinpoint. You get that feeling. I had that feeling getting into the arena. I felt like, ‘I am about to step onto that ice, and if I can work through it, my life will change forever.’”

The epochal Swan Lake costume is hiding in Baiul-Farina’s closet, while her gold medal is locked in a safe. Although Baiul-Farina said she missed the opening and closing ceremonies, she did enjoy the athlete’s village. She noted that each country boasted its national dishes.

The epochal Swan Lake costume is hiding in Baiul-Farina’s closet, while her gold medal is locked in a safe. Although Baiul-Farina said she missed the opening and closing ceremonies, she did enjoy the athlete’s village. She noted that each country boasted its national dishes.

“In the village, each country had their own section,” she explained. “I loved going to eat because they had so many different cuisines there. In figure skating, you always have to watch your weight. After I was injured, I didn’t think I would pull through. I went and had chicken legs. I felt so full and was happy. I came home, put my makeup on and went to the building.”

The golden age of skating

Another unique angle of the Lillehammer Games is that it was the first time that rules were relaxed to allow professionals to compete. Katarina Witt, Brian Boitano, plus Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean were all reunited with Olympic ice. Baiul-Farina glows at the memories of competing with athletes of that era, naming a list of others.

“After the Olympics,” she added, “I have known all of those people. And I have worked with many skaters, and 30 years later, what I can say is that all of those skaters are so authentic. They are the best in the business. They all brought a lot to the figure skating world and a lot of change. From that Olympics, a lot of people still do know a lot of names. If you ask someone who doesn’t watch figure skating, and you ask ‘Who do you know?’ those are the names that usually come up. It feels like I hit the jackpot at that Olympics because I was young enough to be able to compete. I was transformative for the world of figure skating. I did that Swan performance that everyone was wanting to copy. Those ’94 Olympics are portrayed as a negative thing, but they brought so much positive to the world of skating.”

Current figure skaters are taking the sport to record heights, executing elements that were thought impossible in the 1990s. However, it’s not the quads that catch Baiul-Farina’s eye. The artistry is front and center for her.

“The most important thing for the youngsters,” she continued, “is to be authentic. When I am watching figure skating, I am not watching who can jump more jumps. I was taught figure skating is not figure jumping. Figure skating is about beauty, artistry and history. Before me, there was so many wonderful other names who are innovators. I love Jason Brown, and those people to me are the reason I would watch figure skating- to be authentic. We did our part in the world of figure skating, but don’t try to be like we are, try to be better than we are.”

The images of Baiul-Farina from Lillehammer will last forever. While the world has changed, her name still carries an iconic value that can’t be purchased.