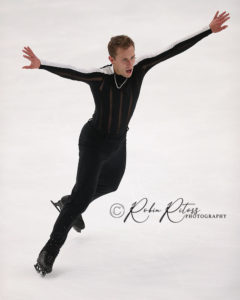

By Claire Cloutier, Team FSO Contributing Writer

Photos courtesy of Robin Ritoss and Michal Brezina

NORWOOD, Mass. – At 31, Michal Brezina stands at the crossroads of a skating life. The veteran Czech athlete is still competing and aiming for his fourth Olympic Games this February. Meanwhile, he has started an active coaching career in southern California, where he trains.

Brezina is also combining parenthood with skating and work. His wife, former Israeli skater Danielle Montalbano, gave birth to their daughter Naya Rose in February 2020. “She’s running now and talking. It’s fun,” Brezina said of his daughter. “Dani and I are both at the rink all day. So she goes to day care. Sometimes, it’s kind of sad, because we both feel like we’re missing out on certain things. But we try to make as much family time as we can. So I coach, and I skate, plus I’m trying to put [fatherhood] into it. It’s challenging, but it keeps me going.”

Brezina is also combining parenthood with skating and work. His wife, former Israeli skater Danielle Montalbano, gave birth to their daughter Naya Rose in February 2020. “She’s running now and talking. It’s fun,” Brezina said of his daughter. “Dani and I are both at the rink all day. So she goes to day care. Sometimes, it’s kind of sad, because we both feel like we’re missing out on certain things. But we try to make as much family time as we can. So I coach, and I skate, plus I’m trying to put [fatherhood] into it. It’s challenging, but it keeps me going.”

Brezina’s competitive skating journey is winding toward its end, even as other paths open. Yet, he is still finding new ways to move forward and approach his training.

He opened his season earlier this month by winning the U.S. International Figure Skating Classic senior B event in Norwood, Mass. Although he has earned many Grand Prix and Challenger Series medals in competition over the past decade, this was Brezina’s first outright victory in an international event since the 2013 Slovenia Cup. It was a positive start to a season that Brezina hopes will allow him to “finish my career on a good note” at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

In Norwood, Brezina landed a quad Salchow and triple Axel in each program to help secure the victory. “There’s still things that need work, obviously,” he said after the long program. “I was a little bit slow. I think I skated a little bit carefully.”

Brezina said that one of his goals for the season is to “stay healthy.” Now that he is a bit older, and perhaps more prone to injury, he has changed his approach to practicing jumps. “I’m working on a lot of basics. I’m trying not to jump as much,” he explained. “I’m trying to modify my practices so we do more skating. Then, when I do the heavy jumps like quad Salchow, and when we work on quad toe [loops], it’s a little bit easier. I tend to do a lot more triples, and just make them bigger, so I know I have the space to rotate.”

The Czech skater has always been known for his strong jump technique, particularly on his triple Axel. Brezina reflected on how he learned that technique from Karol Divin, the 1960 Olympic silver medalist and one of his early coaches. “Mr. Divin was the guy that I mainly learned with when I was younger, because he lives in my hometown [Brno, Czechoslovakia],” Brezina recalled. “I was lucky enough that he was still coming to the rink every day [then].”

One of Divin’s trademark moves was his flying sit spin. “He had a really good technique for his time,” Brezina noted. “That is the main reason why my Axel is the way it is still, to this day. If you know how to teach a flying sit spin, you know how to teach a triple Axel. Because the takeoff is exactly the same.” Now that Brezina is a coach, he hopes to pass on the technique he learned from Divin to his own students.

In addition to modifying his jump approach, Brezina has also added another new element to his training. For the first time in his skating career–which spans 25 years–he is working with a mental health coach. Brezina said that it’s had a significant effect on his skating.

“It’s important. I never thought that it was [before],” Brezina admitted. “I would say right now, it’s a big part of the [coaching] team.”

His work with the coach began last spring after the 2021 World Championships, when the Czech skating federation hired a mental health counseling firm to consult with the Czech figure skaters. “They said: ‘We signed a contract, and it would be nice if you talk with him [and] schedule an evaluation,’” Brezina said.

“The first test he gave me was assigning colors to words. When you see a word, click a color as you think about it,” Brezina explained. “When he called to talk about the results [of the evaluation], I was amazed how he could get all of this [analysis] from looking at colors. When I talk to him, I realize that whatever goes on in my head, you can see through my movement, the way that my eyes work, or my facial expressions. It’s very interesting.”

Brezina meets regularly with the mental health coach. “The main problem was that I always used to tell myself, ‘I have to do this,’ instead of, ‘I want to do this,” Brezina shared. “It brings you down. Telling yourself, ‘I want to do this,’ because you do it every day, and you just want to have fun with it, gives you a different energy.”

The counseling work supports his regular training with coach Rafael Arutunian. “Rafael, and his persuasive talking, and making you do things the way that he wants things done, I already understand,” said Brezina. “It’s just finding the mental strength to do it, even when you’re tired, or you might be nervous. Working with the mental health coach helped a lot. When I talk to him, it makes me realize that you don’t have to be perfect. For athletes on our level, sometimes we think we can do it [all] ourselves. You can’t. Sometimes there’s something in your heart that just doesn’t allow you to get over that hump–until you talk to someone who explains it in a different way.”

At U.S. International Classic, Brezina tweaked his back in practice after the short program and felt worried. “I called [the coach] right after,” Brezina said. “He made me realize that it’s not important. You practiced for this. The fact that your back hurts a little should not change your mental preparedness for the competition.” He rallied to deliver a good, if not perfect, long program.

Brezina admitted that he wonders how his career might have been different, had he begun working earlier with a mental health coach. “Who knows where I could have been, if I had him at Worlds last year?” Brezina pondered. “Or at 2020 Europeans, when I was first after the short [program]? Or when I was second in the [short program at 2012 Worlds] in Nice? I went into it like: ‘I need to prove something, and I need to show everybody.’ If I’d had someone who could tell me: ‘Listen. Just enjoy it. Don’t think about what you’re doing. Think about how you’re doing it.’”

But there’s no turning back. So Brezina focuses on the future. “Every competition, I’m just trying to see [what to] work on,” he said. “To make sure that when I go to the Olympics, I skate not even for a result, but just to skate, to make myself happy, to know that I did everything in my own possibilities, to skate the best that I could.”

That’s the Olympic moment that Michal Brezina is hoping for.